Recently, we have come across a new word for raw material used in flag production. Although it is a common word for describing a neutral colour, it is also an adjective applied to cloth taken straight from the loom in an un-dyed, unbleached state. Griege, pronounced ‘grey,’ is a variable between beige and grey and can be dyed to any colour by the dyers, using sophisticated machinery, specialist techniques and a wealth of expertise. Today’s modern machinery and computer-assisted design led us to ponder how flags and banner fabrics were dyed in days gone by. Most notably, in the medieval period when flags were so important and possibly only ever commissioned by the very wealthy.

So how was fabric dyed then? It appears that the fabric was dyed near running water using natural dyes derived from various roots, lichens, minerals and more. The fabric was soaked in the solution and agitated many times before being ‘fixed’ with alum. The fabric was almost certainly dried outside in the heat of the day as were laundry and animal hides. Kilns were not invented until a later date. Just as flags are today, medieval flags were very colourful but only the wealthy could purchase such luxuries. Many flags and personal arms were resplendent with rich blues, crimson reds, greens, yellows and the most expensive of all, black. It seems that wool and cotton were the main fabrics at the lower end of the scale. However, the dyeing process for the more luxurious side such as silks, satins and velvet used more specialist techniques. This was due to the different up-takes of fabric fibres. For instance, the shade would be paler, especially with silk, than the same process used to dye coarse cloth.

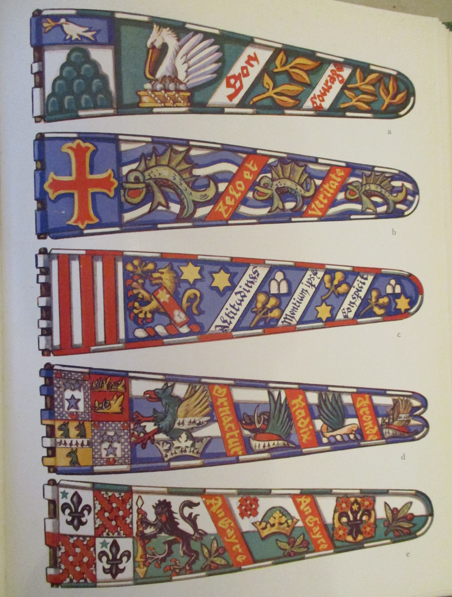

The most difficult colour fabric dye, just as it is today, was black. Even for the wealthy, only the seriously rich could afford this luxury. When perusing the colour plates of the heraldic standards from the medieval period, it was notable that black was barely represented. Flag production has certainly moved on.